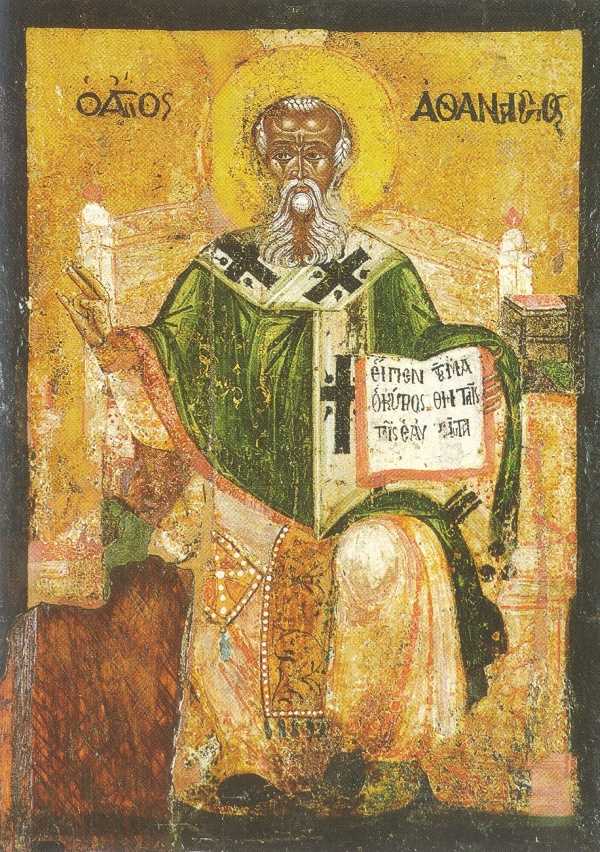

Athanasius of Alexandria (abt AD 296-372) is one of the most significant theologians of the golden age of patristic thought. He served as deacon and secretary to Bishop Alexander of Alexandria, and in that capacity Athanasius attended the Council of Nicaea (AD 325). With the death of Alexander (AD 328), Athanasius was elected to succeed him. He was a giant of the Faith who engaged in theological controversy and political intrigue with emperors and bishops in defense of Nicene orthodoxy. He was known as a man of fiery and uncompromising disposition, expressed in the maxim “Athanasius against the world!”

Athanasius wrote On the Incarnation of the Word to defend against the teachings of Arius. Arius, also a deacon of the Alexandrian church, insisted that the Word of the Father was created by the Father, similar to the Father in substance, and therefore subordinate to the Father. The Word is god, but not consubstantial with the Father. The transcendence of the Father required the inferiority of the Word to effect the incarnation because the uncreated and eternal God could not assume that which is created and temporal. The Word is not divine by nature, but by the gracious will of the Father. Arius insisted that only that which is created can unite with creation, only that which is creature can become incarnate.

Both Athanasius and Arius were likely baptized according to the common Trinitarian rite of the church; and both confessed that Jesus Christ is the Son of God who died, and was raised from the dead for the salvation of humanity. Both parties were Christian. But they had profound differences on the nature of the Godhead and what it means to be the Son of God. The question is sometimes asked, “Do these theological distinctions really matter?” Athanasius would respond that these theological distinctions are essential to the salvation of the world.

Athanasius’ thesis may be summarized in the words “For [the Word] was incarnate that we might be made god.” An exposition of this statement must answer the following questions: What is the nature of the Godhead? What is the relationship between God and creation? What is the human problem? What is the incarnation? How does the incarnation provide a remedy for the human problem?

The issue at hand is the divinity of the Son. Both Arius and Athanasius believed that the Son is divine. However, Athanasius is determined to declare the full divinity of the Son. The Son is the “incorporeal and incorruptible and immaterial” image of the Father. The Son is “all-holy” and omnipresent. The Son shares the power and wisdom of the Father. We can get a better sense of what Athanasius meant by image as we consider his other writings. For example, in Against the Gentiles, He wrote,

[The Son] is the Power of the Father and his Wisdom and Word; not so by participation, nor do these properties accrue to him from outside in the way of those who participate in him and are given wisdom by him, being strong and rational in him; but he is Wisdom-in-himself, Word-in-himself, himself the Father’s own Power, Light-in-himself, Truth-in-himself, Righteousness-in-himself, Virtue-in-himself, yes, and the Stamp and Effulgence and Image. In short, he is the supremely perfect fruit of the Father, and is alone Son, the exact image of the Father.[1]

The simplicity of God requires that the Son is not part of the Father, but the fulness of the Father. The Son is “in his own Father alone wholly and in every respect” (emphasis added). The divine attributes of the Son are not imparted from the Father, but are essential to the Son’s being. The Father and the Son share the same divine substance, or character, and are therefore equally God.

Creation is ordered and given life by the Father through the Son. The Son is the mediator of creation. God (Father and Son) has created the cosmos “out of nothing.” Whereas creation is dependent on the Father, likewise creation is dependent on the Son, and there is no ontological distinction of divinity, power, or glory in Father and Son. The Son transcends creation and is in no way dependent on creation. All creation is filled with the presence of the Son, and bears witness to the Son. It is the Son’s presence in creation that makes the incarnation possible.

In fact, creation anticipates the incarnation. Like all creation, God created humanity out of nothing, but differentiated humanity from all other creatures. Humans were “called into being by the presence and loving-kindness of the Word.” God has graciously endowed humanity with “his own image, giving them a portion even of the power of his own Word” so that humans are a reflection of the Word, and share in the rationality of the Word. Because humanity is created, humans are mortal. However, because humans bear the image of God and share in the rationality of the Word, as long as they maintained the “contemplation of God” they would “abide ever in blessedness” and incorruption. Athanasius declared, “For because of the Word dwelling with them, even their natural corruption did not come near them.” The words “natural corruption” speak to human mortality. Because humans were created in the image of the Word, the Word can assume human nature in the incarnation.

God created humans in “his own image” as rational beings. This implies human freedom of will. Because “the will of man could sway to either side,” God established humanity in “his own Garden” with divine law to encourage righteousness. However, humans “despised and rejected the contemplation of God,” and became “corrupted according to their devices” which left them “bereft of the knowledge of God.” The penalty of disobedience is “to abide in death and in corruption.” Fallen humans have an insatiable appetite for sinning and are caught in an ever-descending spiral of corruption, violence, crimes against nature (sexual immorality), and idolatry. The corruption of sin is so devastating that “the race of man was perishing; the rational man made in God’s image was disappearing, and the handiwork of God was in process of dissolution.” Sin has so corrupted the created order that creation is being chaotically deconstructed and moving towards “non-existence.”

The incarnation of the Son is inextricably linked to the creation of humanity. Humans were created to share the rationality of the Word, and therefore “the renewal of creation has been the work of the selfsame Word that made it at the beginning.” For this cause the eternal, incorruptible, and incorporeal Son “comes in condescension” to take upon “himself a body. . . of our kind.” The Son has created a human body to be nourished in the womb of “a spotless and stainless virgin” and subject to the penalty of corruption and death. Therefore, in union with human nature, God the Son experiences the totality of human suffering from birth to death. For Athanasius, the incarnation is not limited to the conception and nativity of the Son, but speaks to the totality of the Son’s redemptive work – nativity, teaching, crucifixion, and resurrection. The immortal Word is united with mortal humanity and that union makes the assumed human nature “worthy to die in the stead of all.” The cross is Christ’s trophy of his victory over death. This can be accomplished only by the incarnate Son who is simultaneously consubstantial with the Father and with humanity. The death of the incarnate son is a substitutionary sacrifice that is offered for the satisfaction of a debt. The Lord and Savior of all has “blotted out the death which had ensued by offering his own body” for the restoration of humanity and the renewal of creation. This is made possible only “by the presence of the very image of God” who is “able to create afresh” humanity after the divine image. Athanasius has declared that Arius’ created Word who is of similar nature to the Father is incapable of defeating death and renewing creation because he is neither fully God, nor absolute Creator. “None other, then, was sufficient for this need, save the image of the Father.” Jesus Christ is “not man only, but also. . . true God.” The incarnation of the Son in no way diminishes his deity. “For no part of creation is left void of Him: he has filled all things everywhere, remaining present with his own Father.” Athanasius speaks of the incarnation of the Word in terms of “being made man,” “taking to himself a body,” “appearing in a body,” and “becoming a man.” The human body is a “temple,” “instrument,” and dwelling. There is no explicit consideration of the Word assuming human nature in totality – flesh, spirit, soul, and will. However, the incarnation is not a mere appearance of the Son, but the assumption of a body of our kind. The full divinity of Christ is explicit, the full humanity of Christ is implied.

The purpose of the incarnation is that humans might be made god. God’s purpose in creation was that humans would share the rationality, incorruption, and blessedness of the divine image. Through the grace of the resurrection of Christ death is abolished and humanity is clothed with incorruptibility. Furthermore, the resurrection of Christ fills all creation with his divinity and the true revelation and knowledge of the Father and the Son (and the Spirit). The incarnation means that the divine image in humanity is restored and humans can live in joyous contemplation of God in a new creation.

[1] Athanasius, Against the Gentiles, 46. Cited in: John Behr, “Introduction,” in On the Incarnation: Translation, ed. John Behr, trans. John Behr, vol. 44a, Popular Patristics Series (Yonkers, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2011), 35.